The intersection of migration and public health is a complex, often charged topic. A recurring concern in public discourse is the idea that asylum seekers and migrants from lower-income countries pose a significant health risk to the UK population, potentially "bringing in" diseases and overwhelming the National Health Service (NHS). This article provides a comprehensive, evidence-based examination of this issue, covering global vaccination disparities, actual disease case data in the UK, the existing health screening protocols, and the tangible pressures on healthcare services.

Global Vaccination Disparities: The Source of Concern

The core of the concern is not without some basis in global health inequity. Many countries of origin for asylum seekers—particularly those experiencing conflict or extreme poverty—do have fragile or incomplete national vaccination programs compared to the UK's well-established system.

- Measles: According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and UNICEF, routine measles vaccination coverage has dropped in numerous countries since the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving millions of children vulnerable. Outbreaks in countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia are regularly reported.

- Diphtheria: Similarly, diphtheria remains a threat in regions with low DTP (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis) vaccination coverage. Outbreaks have been documented in refugee camps and densely populated settlements with poor sanitation.

- Other Diseases: Diseases like polio, while eradicated in the UK, remain endemic in two countries (Afghanistan and Pakistan), and tuberculosis (TB) incidence rates are significantly higher in many parts of Africa and Asia compared to Western Europe.

It is accurate to state that individuals arriving from areas with ongoing outbreaks or low vaccine coverage may have a higher personal risk of carrying or being susceptible to certain communicable diseases.

UK Health Screening and Initial Assessment

The UK has specific protocols to manage public health risk at the border, though they are targeted rather than universal.

- Pre-arrival Screening: Some resettlement schemes (like the former UK Resettlement Scheme) include mandatory health assessments overseas, including for TB.

- Port of Arrival: Medical inspectors from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) can be called to assess anyone arriving who appears unwell.

- Asylum Seeker Initial Assessment: Once in the system, asylum seekers are offered an initial health assessment by a GP. This is not a compulsory detailed screening for all diseases but aims to identify immediate needs, offer relevant vaccinations (like MMR), and provide TB screening for those from high-incidence countries.

The Gap: Critics argue this system is reactive and piecemeal, potentially missing asymptomatic carriers or those with conditions not immediately visible. The lack of comprehensive, mandatory screening for all entrants is often cited as a vulnerability.

Impact on UK Disease Epidemiology and the NHS

Disease Transmission: What Does the Data Show?

While isolated cases and small outbreaks linked to importation do occur, the overall impact on UK disease rates is nuanced.

- Measles: Recent UK outbreaks (2023-2024) have been primarily driven by domestic under-vaccination. UKHSA data consistently shows that low MMR uptake in certain communities within the UK is the primary risk factor for sustained transmission. Imported cases can spark an outbreak, but it cannot spread widely without a susceptible local population.

- Diphtheria: Small numbers of diphtheria cases are recorded annually, often linked to travel or migration. A 2022 outbreak among asylum seekers in temporary accommodation was contained through isolation and treatment.

- TB: TB rates in the UK are overwhelmingly concentrated in urban areas and among non-UK born populations. However, active TB is not easily transmissible (requiring prolonged close contact), and the BCG vaccine offers some protection. The NHS focuses on case finding and treatment within at-risk communities.

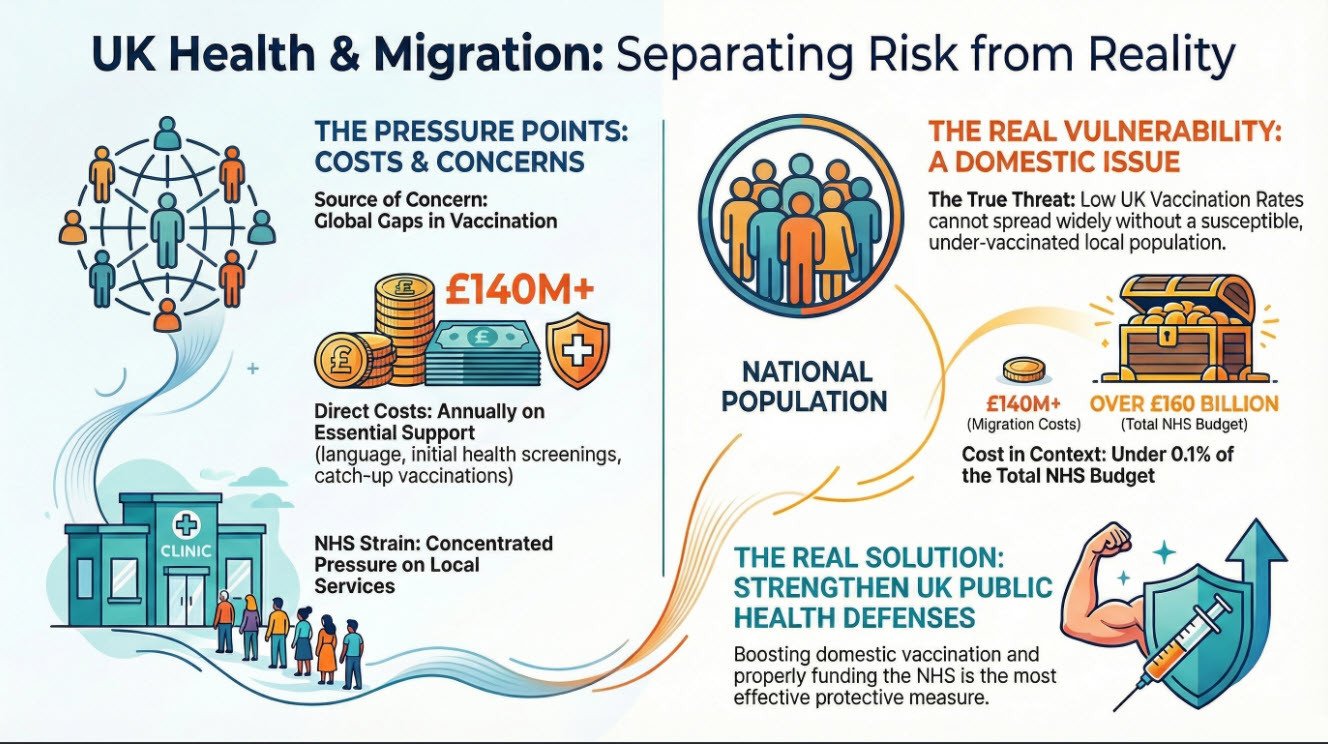

Key Conclusion: The principal public health threat arises at the intersection of imported cases and gaps in domestic herd immunity. The UK's own falling childhood vaccination rates create a far larger susceptible pool for any introduced pathogen to exploit.

Pressure on Doctors and Hospitals

The strain on the NHS from migration is a matter of capacity and systemic pressure, often distinct from disease outbreaks.

- Immediate and Complex Needs: New arrivals, especially those from conflict zones or arduous journeys, often have unmet health needs. This can include untreated chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension), mental health trauma (PTSD, depression), and wounds or infections. Addressing these requires significant GP and specialist time initially.

- Language and Cultural Barriers: Consultations take longer, requiring interpreters and cultural mediation, slowing down service throughput.

- Concentrated Pressure: As asylum seekers are often housed in specific localities, pressure can fall disproportionately on certain GP practices and local hospitals, challenging already stretched resources.

- Long-Term Impact: Once initial needs are addressed and individuals are integrated into the NHS system, their health profile and usage patterns tend to converge with those of the general population. They are typically young and, aside from initial conditions, can have lower long-term demands for age-related care than an ageing native population.

Future Considerations: "Explosive Growth" and Systemic Resilience

Projections of future migration are uncertain, but preparedness is key. The future impact depends less on absolute numbers and more on:

- UK Vaccination Rates: Reversing the decline in childhood MMR and other routine vaccine uptake is the single most effective measure to protect the population from any imported infectious disease.

- Screening and Integration Policies: Enhancing initial health assessments to be more comprehensive, with faster linkage to GP registration and vaccination services, would mitigate risk and improve individual care.

- NHS Funding and Capacity: Pressures from migration are a subset of the wider crisis in NHS funding, staffing, and social care. A resilient, well-funded system can absorb demographic fluctuations; an overstretched one will struggle with any additional demand.

- Global Health Solidarity: Supporting vaccination programs and health systems in source countries is both an ethical imperative and a component of long-term UK health security.

The Financial Burden: Interpreter Services and Initial Healthcare Costs

A significant and often debated aspect of providing healthcare to migrants and asylum seekers is the direct financial cost to the NHS. This encompasses both the essential service of language interpretation and the immediate costs of treatment and prophylaxis. Understanding these figures is crucial for an honest assessment of impact.

1. The Cost of Language Interpretation in the NHS

Effective communication is a clinical and legal necessity. The NHS is legally obligated under the Equality Act 2010 to ensure patients can understand their diagnosis and give informed consent. For non-English speakers, this requires professional interpreters.

- Scale of Spending: Exact nationwide figures are notoriously difficult to pinpoint due to decentralized procurement by individual NHS trusts and GP federations. However, investigations and Freedom of Information (FOI) requests have revealed substantial expenditure.

- Trust-Level Data: In 2022, an investigation by The Independent found that NHS trusts in England spent over £100 million on translation services and interpreters between 2019 and 2022. For example, one major London trust reported spending over £5 million annually on these services.

- GP Practice Costs: At the primary care level, the cost is also significant. A 2023 report by the group Migration Watch UK, based on FOI data, estimated that GP practices in England spend approximately £40 million per year on interpretation and translation. This includes in-person interpreters, telephone services (like the BigWord and LanguageLine), and translation of documents.

- Breakdown and Justification: Critics argue this is a preventable drain on resources. However, health economists and clinicians counter that these costs are offset by preventing far more expensive outcomes. Misdiagnosis, incorrect medication use, missed appointments, and the clinical risks of untreated conditions due to miscommunication lead to higher A&E attendances, hospital admissions, and long-term complications. Professional interpretation is a cost-effective measure for patient safety and efficient service delivery.

2. The Cost of Initial Treatment, Drugs, and Vaccinations

Asylum seekers and undocumented migrants are entitled to free NHS primary care (GP and nurse consultations, treatment for infectious diseases) and emergency care. They are not entitled to non-urgent secondary care without charge, though often receive it. The initial health phase involves specific costs:

- Vaccination Program Costs: The most significant pharmaceutical outlay is for catch-up vaccinations. A standard course of the MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) vaccine costs the NHS approximately £15-£20 per dose (two doses are required). The 5-in-1 vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, and Hib) costs around £25-£30 per dose. While these are routine costs for any unvaccinated individual, a sudden influx of a large cohort requires bulk purchasing and additional administrative and clinical time to deliver.

- TB Screening and Treatment: Screening for Latent TB Infection (LTBI) with an Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) blood test costs £80-£100 per test. Treating active TB is far more expensive, involving a multi-drug regimen over 6+ months and potential hospitalisation. A single case of multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) can cost the NHS £50,000 - £100,000+ to treat.

- Parasitic Infections and Other Conditions: Treatment for conditions like scabies, threadworm, or chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension discovered during initial assessment adds to pharmacy budgets. The antibiotic course for bacterial infections, wound care, and mental health medications (e.g., antidepressants for PTSD) constitute the standard drug tariff costs but are multiplied by volume.

- The "Hotel" Outbreak Factor: The accommodation of asylum seekers in contingency settings like hotels has led to concentrated disease outbreaks (e.g., diphtheria, scabies). Containing these requires rapid, on-site public health interventions—mobile vaccination clinics, mass distribution of medication, and environmental cleaning—which incur exceptional, unbudgeted costs for local NHS teams and UKHSA.

Total Annual Cost Estimation

Providing a single, precise national figure is impossible due to fragmented accounting. However, a conservative annual estimate for these direct costs related to migrants and asylum seekers would be in the high tens to low hundreds of millions of pounds.

- Interpretation: ~£50-£80 million (across primary and secondary care).

- Initial Vaccination & Screening Programs: ~£20-£40 million (dependent on annual intake numbers).

- Acute and Outbreak Management: Variable, but significant at a localised level.

Crucial Context: This cost must be weighed against:

- The NHS's Overall Budget: The NHS England budget for 2023/24 is over £160 billion. The estimated migrant-related costs, while substantial, represent a very small fraction (<0.1%) of total expenditure.

- Cost Avoidance: Early intervention through GP registration and vaccination prevents the astronomically higher costs of managing disease outbreaks, complex emergencies, and long-term disability in an unvaccinated population.

- Fiscal Contributions: Many migrants, once granted status and entering the workforce, become net contributors through taxation and National Insurance, which funds the NHS. The initial healthcare cost is an investment in a future taxpayer's health and productivity.

In summary, while there are undeniable and quantifiable costs associated with providing initial and linguistically accessible healthcare to new arrivals, these are a legally mandated and clinically necessary component of the UK's public health system. The financial debate should centre not on whether to provide this care, but on how to fund and structure it most efficiently within the broader context of an underfunded NHS.

Conclusion

The narrative that migrants are a major vector of disease into the UK is an oversimplification of a multifaceted public health challenge. While genuine risks exist due to global vaccination gaps, and these can manifest in isolated incidents, the data does not support the notion of a large-scale disease threat driven by migration.

The greater vulnerability lies within the UK's own declining herd immunity. The significant pressure on the NHS stems primarily from systemic issues of capacity and funding, exacerbated by the concentrated initial needs of new arrivals. A robust response requires a dual focus: strengthening the UK's domestic public health defenses through vaccination and a resilient NHS, while implementing more coherent and proactive health screening and integration pathways for new arrivals. Public health protection is best achieved through evidence-based policy, not fear-based rhetoric.

Sources & Further Reading:

- UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). (2024). Confirmed cases of measles, mumps and rubella in England. Official statistics.

- UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). (2023). Tuberculosis in England. Annual report.

- World Health Organization (WHO) & UNICEF. (2023). Progress and Challenges with Measles and Rubella Elimination. Immunization data.

- Migrant Health Guide. (2023). Public Health England (archived resource now under UKHSA).

- The Health Foundation. (2022). Use of health care by migrants and visitors. Analysis brief.

- The BMJ. (2022). Diphtheria outbreaks in asylum seekers in the UK. News analysis.

- National Health Service (NHS). (2023). Guidance on the healthcare needs of migrant patients.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2024). Global immunization coverage. Data dashboard.

Disclaimer: For important information regarding the sourcing, purpose, and limitations of this content, please refer to the full disclaimer located in the footer of this website.

If you want assistance with this article, please Contact Us