Introduction

Security assurances provided to the public regarding the "One Login" system re digital ID are described as being worthless, casting a shadow over the government's digital ambitions.

It is argued that Sir Keir Starmer may not have fully grasped the troubled state of the national digital ID programme he announced in just 26 seconds on a Friday afternoon. Despite No 10’s pledge of a system built "with security at its core," information emerging from the project suggests the complete opposite.

The fundamental strategy for implementing digital ID appears to be based on a simple assumption: since millions of people are already being enrolled in "One Login," a system initiated by Michael Gove, only minimal legislation would be required to finalize the project. Labour strategists reportedly proposed rebranding a smartphone application as the "GOV.UK Wallet," designed to function similarly to an Apple or Google wallet.

Digital ID and One Login

This app would be constructed on the existing One Login platform and would hold various credentials, such as a driving licence.2 This approach would effectively introduce a national digital ID system by stealth, without the public fully realizing the transition—a scenario likened to a frog being boiled so slowly it doesn't notice the rising temperature.

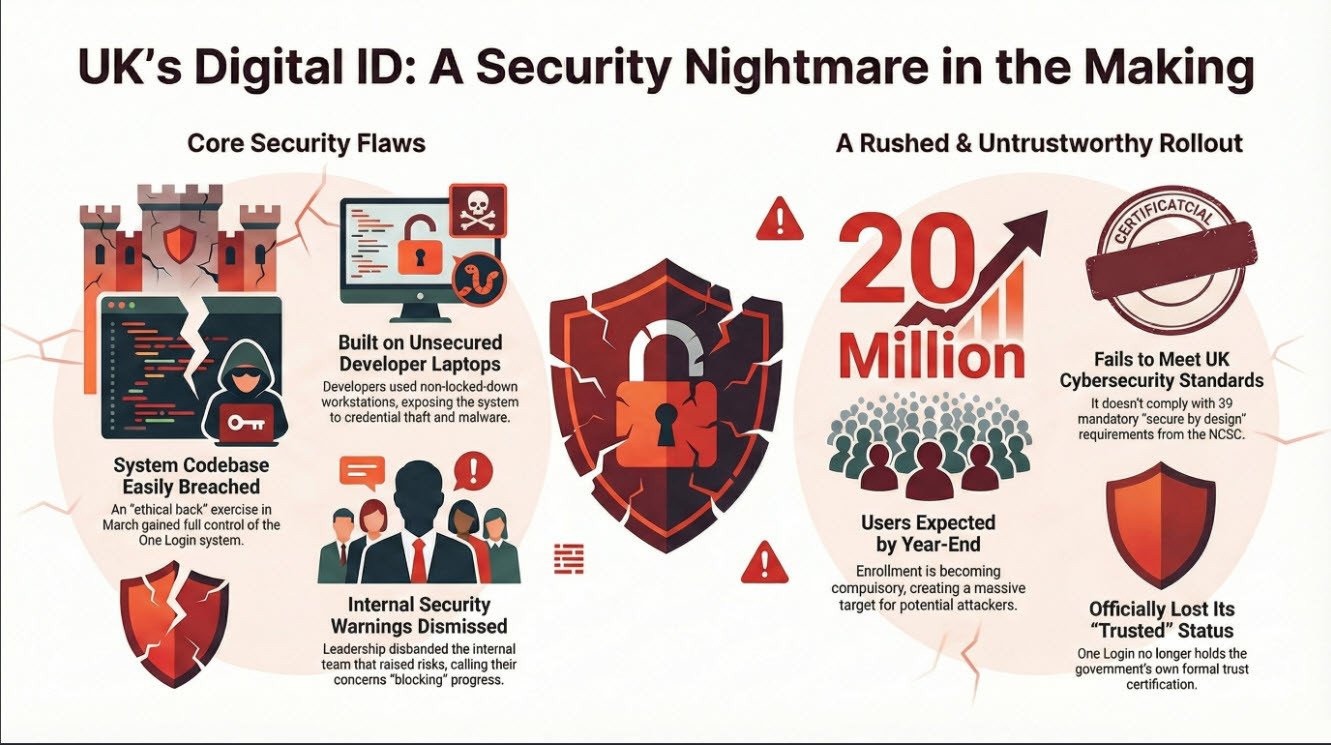

Currently, 12 million One Login identities have been established. This figure is projected to rise to nearly 20 million by the end of the year, as company officers will be forcibly enrolled by Companies House, where the system becomes compulsory on November 18. While this may seem like a clever rollout strategy, the reality, according to the author, is that the system's security guarantees are meaningless.

This assertion is supported by internal events. When risk assessment professionals within the civil service reported to management that the system was being developed on unsecured workstations by contractors in Romania who lacked the required security clearance, the leadership at the Government Digital Service (GDS) reportedly reacted poorly.

Rather than addressing the security flaws, the GDS senior leadership team was allegedly more concerned with reputation management. The team that raised these critical concerns was subsequently disbanded. Tom Read, the GDS chief executive at the time (who has since left for the private sector), is said to have dismissed these security warnings as "blocking" progress.

Furthermore, One Login is not even classified as a safe or trusted identity provider according to the UK government's own official standards. It previously held this status but has since lost its formal trust certification, which is issued under the same government framework used to approve private-sector identity companies like Yoti.

One specific, critical security failure highlighted is the failure to lock down the computers used for development. This basic security measure, known as maintaining "privileged access workstations" (PAWs), would prevent developers from accessing consumer websites like TikTok or personal email, both of which expose a device to risks like session hijacking or credential theft.

See David Davis MP explaining the lack of security of the proposed Digital ID system

The GDS, however, has traditionally "frowned upon" such a locked-down security culture and has never maintained a dedicated pool of PAWs. This failure had significant consequences. In March, "hackers" were able to use an unsecured laptop to "browse up"—or escalate their privileges—and gain control of the One Login codebase, allowing them to embed malicious code deep within the system.

These "hackers" were, thankfully, not hostile state actors but part of a "red team exercise," a planned stress test where a contractor simulates an attack. While no actual malware was buried, the exercise demonstrated a critical vulnerability. It raises the disturbing possibility that genuinely hostile parties, such as those from China or Iran, may have already exploited this same "apparent ease" of access.

Say no to Digital ID?

Following reports in The Telegraph detailing these security concerns in April, GDS was reprimanded. Incredibly, however, the organization still allegedly cannot guarantee that devices are locked down or prevent contractors—who perform the bulk of the work—from using unauthorized devices. The government also lacks a specialized IT team to build and maintain these essential PAWs.

This security crisis is compounded by bureaucratic chaos, as GDS is in the process of being moved from the Cabinet Office to the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT).3 This move, announced 15 months ago, is still only "underway," leaving some staff to use two separate laptops.

In response to these issues, a DSIT spokesperson stated: "GDS has a robust device management policy, with all members of the team working on One Login required to use a corporately managed device. GDS-managed devices are monitored by a central security team to detect any malicious activity."4

However, insiders reportedly dismiss this "policy" as merely "a piece of paper," pointing out that this supposedly "robust" system failed to even notice the red team's successful hijack of the system in March.

By contrast, Estonia's digital ID system is considered by security experts to be one of the world's most secure designs—and even it has been hacked. One Login is described as "nowhere near as secure." It reportedly fails to comply with mandatory "secure by design" principles and does not meet the 39 requirements of the National Cyber Security Centre’s Cyber Assessment Framework.

GDS has promised to meet this framework by the end of 2025, but the author argues there is "no way" it can meet this promise given its inability to even secure its own development equipment. The article concludes that the digital ID initiative continues to move forward, a disaster apparently obvious to everyone except No 10.

Pure Coincidences

Check out this video explaining 'pure coincides' and make up your own mind!

If you require assistance with this article, please contact us.