The white cliffs of Dover have stood for centuries as a symbol of Britain’s island fortress identity. Yet, today, they bear witness to a relentless, desperate phenomenon: the daily arrival of flimsy, overcrowded dinghies carrying migrant men, women, and children from the world’s conflict zones and poorest nations. The English Channel, one of the world’s busiest and most treacherous shipping lanes, has become the unlikely frontier of the UK’s illegal migration crisis. The official numbers are staggering and speak to a system buckling under immense pressure.

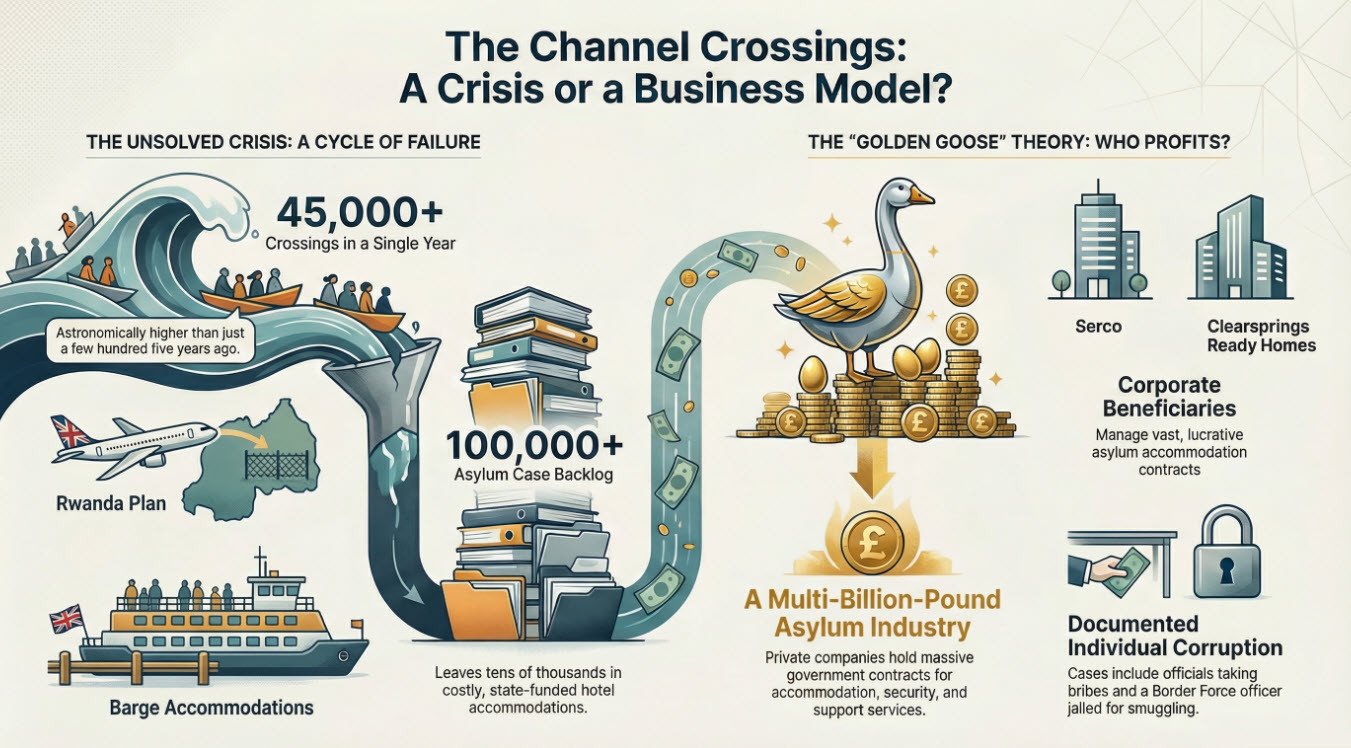

In the past year, despite lofty government promises to "stop the boats," over 45,000 people made the perilous crossing. This figure, while a slight decrease from the previous year’s record, remains astronomically higher than the few hundred who attempted the journey just half a decade ago. Each digit in that tally represents a person, often with a devastating story, who has paid criminal gangs thousands of pounds for a spot on a boat with no guarantee of safety.

This raises a perplexing, central question: if these individuals are fleeing poverty with no financial resources, as the data suggests, how are they funding a journey that can cost upwards of £5,000 per person? The simple, grim answer is through debt bondage, family liquidation, and years of savings. Yet, this economic puzzle has fuelled a more sinister narrative in the corners of public discourse.

A vocal cohort of conspiracy theorists alleges a hidden hand guiding this traffic. They posit that the scale and persistence of the crossings, in the face of apparent state capability to stop them, point to complicity. The theory suggests that the UK government itself, or powerful actors within its orbit, is facilitating—or at least deliberately not preventing—the influx. While dismissed outright by officials, this claim gains traction when viewed alongside what many see as the government’s poor and performative attempts at solutions.

The policy response has been a cycle of announcement, backlash, and legal obstruction. The flagship Rwanda asylum plan, announced with great fanfare, has spent years and millions of pounds entangled in court battles without a single flight taking off.

The deal to house migrants in barges and former military bases, like the now-notorious Bibby Stockholm, has been mired in controversies over cost, safety, and suitability. The promised "pushback" tactics for boats at sea have barely materialized, deemed too dangerous by operational commanders. Meanwhile, the asylum backlog has swollen to over 100,000 cases, leaving tens of thousands in costly, state-funded hotel accommodation—a fact the government laments but seems unable to resolve. This cycle of failure leads critics to ask: is this incompetence, or is there a deliberate lack of will?

Here, the conspiracy theorists weave a narrative of profit motive. They allege that the crisis has become a "golden goose" for a constellation of private companies holding massive government contracts. The asylum accommodation and support system is a multi-billion-pound industry.

Firms like Serco and Clearsprings Ready Homes are paid vast sums to manage accommodation, from hotels to controversial asylum centres. Contracts are awarded without competitive tender under emergency provisions, and costs per person per night run into the hundreds. Security firms, catering companies, legal services, and transport contractors all form part of a vast, lucrative ecosystem built around the asylum population.

The theory goes further, suggesting that shareholders and investors in these companies—a group which could indirectly include pension funds and individuals across the political and economic spectrum—have a vested financial interest in maintaining a high, steady flow of people requiring detention and processing.

To truly "stop the boats," the argument follows, would be to kill a multi-billion-pound revenue stream. It creates a perverse incentive: the problem must be managed, but never solved. This narrative paints a picture where humanitarian crisis translates into corporate profit, and political rhetoric about control serves as a smokescreen for inaction that benefits the bottom line.

The Migrant Situation

So, how do we separate alarming possibility from unsubstantiated conjecture? The profit motive within the system is an verifiable fact, not a theory. The National Audit Office has repeatedly criticised the Home Office for poor financial oversight and value for money in its migrant asylum contracts. The explosive growth in outsourcing this function has created powerful corporate stakeholders. Whether this translates into active conspiracy is another matter.

The government’s failures are more plausibly explained by a toxic mix of administrative incompetence, legal reality (the UK is bound by international refugee conventions), the complex global forces driving displacement, and the ruthless entrepreneurship of smuggling networks adapting to every new policy.

However, the persistence of the "golden goose" theory is a symptom of a profound breakdown in public trust. When citizens see record numbers arriving, hear constant promises of change, and yet witness only ever-increasing expenditure and corporate enrichment, cynicism flourishes. It becomes easier to believe in a shadowy plot than in serial, systemic failure.

The government’s challenge is therefore twofold: it must develop genuinely effective, humane, and legally sound policies to manage migrant influx and dismantle smuggling networks. But perhaps more urgently, it must dismantle the architecture of perceived profiteering. This requires radical transparency in contracts, a demonstrable shift from costly emergency outsourcing to efficient, publicly accountable systems, and a clear, evidence-based narrative that separates the undeniable human need of refugees from the criminal enterprise of smuggling.

The small boats in the Channel are more than vessels; they are symbols of a world in disorder, of European policy paralysis, and of a British political debate poisoned by failure and suspicion. Until the government can prove through action and transparency that its primary motive is solving the crisis—not managing a lucrative, endless loop of it—the whispers of complicity and profit will continue to echo, undermining the social contract and any potential for a reasoned solution. The cliffs of Dover deserve a better story.

Addendum: The Allegations of Individual Corruption

Beyond the theorized corporate profiteering, a darker, more granular layer of alleged exploitation exists: individual corruption. Investigative reports and court cases have periodically illuminated a shadow economy where some in positions of authority are accused of illegally monetizing the migrant crisis. This isn't systemic conspiracy, but rather the age-old temptation of graft, applied to a high-pressure, vulnerable system.

There have been documented instances of Home Office contractors and security staff being bribed to provide favourable migrant treatment or information. More seriously, a network within the system itself has been alleged. In 2022, The Guardian reported on a National Crime Agency (NCA) investigation into "corrupt Home Office officials" suspected of taking bribes to digitally alter and approve immigration documents for individuals who had no legal right to remain in the UK [Source: The Guardian, "NCA investigates corrupt Home Office officials over immigration claims," 2022].

Furthermore, in 2023, a former Border Force officer was jailed for smuggling migrants through Heathrow Airport's controls, exemplifying how individuals tasked with security can become conduits for illegal entry.

[Source: BBC News, "Ex-Border Force officer jailed for smuggling migrants," 2023].

There are more stories like this, and a search on google would reveal more results.

These cases, while prosecuted, feed the narrative of a "golden goose" at all levels. Conspiracy theorists extrapolate these proven instances of individual malfeasance to suggest a wider, unexposed network of officials, lawyers, and intermediaries who profit from facilitating the journey or status of migrants for personal gain. They argue that for every caught official, more operate in the shadows, creating a perverse incentive within the bureaucracy itself to maintain a broken system from which illicit side incomes can be drawn.

This amplifies public cynicism, fostering a belief that the failure to stem crossings is not just about incompetence or corporate contracts, but also about silent, personal profits woven into the very fabric of the state's response. While evidence points to sporadic criminality rather than top-down design, each scandal reinforces the perception of a crisis from which too many people, at too many levels, are benefiting.

If you want assistance with this article, please Contact Us